Core Concept: Using Third-Party Data APIs

The topic of Third-Party Data APIs is really too broad to be covered thoroughly here. It is a topic full of nuance and importance, especially for developers creating Data APIs. When designing an API, it is as complex as designing a framework or code library: You are trying not only to solve a problem, but to solve it in a way that is understandable and accessible to everyone.

Luckily, we do not need to design an API for our purposes here. We need only to "consume" an API: That is, we will make requests to an API service and we will receive responses from that service that contain data we can use in our Javascript application. This process requires us to get to know the shape of some data returned from a chosen service, but it does not require us to understand the finer points of how APIs are put together.

Just so we aren't diving in completely blind, we will review some of the basics of how APIs work so that we can more easily understand the directions we see in our chosen API's documentation.

Websites for machines

If you compare human beings and computers, you will notice many differences. In fact, there is not much in common between what a human hopes to get from the world and what a computer hopes to get from a world. (Mostly because computers don't "hope".)

When trying to understand the concept of Data APIs that run on the web, it can be tough to get a mental image of what's really happening. The explanation that has always helped me is to imagine building a website for machines.

When building a website for humans, we care about things like information architecture and clear presentation of content that utilizes visual design to reinforce hierarchy, relationships, and meaning. Machines (computers) also need a solid information architecture, but the way we present data for machines is very different from how we present data for users.

To give machines what they need, APIs respond with information that is structured so it can be interpreted by whatever software is making the request. Typically, this means JSON or XML formatting, which are discussed below. Both of these formats lack the visual component that is essential to delivering information for humans. Machines are terrible at interpreting graphic design, but they are very good at keeping track of intricate hierarchies as long as the structure is consistent and syntactically correct.

When we use APIs we are asking our software to do some web browsing for us, and the information it retrieves makes our own application much more valuable to the humans using it.

REST

There are many kinds of APIs, but the dominant architecture on the web today is called "REST". You may see references to "RESTful APIs" or "REST-based APIs"—these are all ways of talking about an API that uses REST architecture.

REST stands for "Representational State Transfer", and although it sounds quite complex, it's something that you encounter every day. REST is the way the web works, and the concept was, in fact, defined by Roy Fielding (co-founder of the Apache web server project) as he worked on defining the HTTP protocol. REST feels natural on the web because REST is the way the web works.

Requests

REST is an architectural principle based on the client-server model. REST assumes that there is a client (web browser, Javascript app, mobile app, etc.) that wishes to consume data from a server (web server, API service, etc.).

When we make a request to a web server or API service, we are essentially sending our own file of information. The request is structured in a way similar to any HTML response we get. Requests have a "method", "headers", and a "message body". Each of these parts of the request is taken apart and inspected by the web server (or API service) in order to understand how to respond.

Methods

Methods are the "verbs" of the web. RESTful services use the base methods defined in the HTTP specification to handle data. These methods are:

- GET—Retrieves information for the client without altering any data on the server. This is commonly known as the "read" method.

- POST—Creates an entirely new record or data object on the server based on information sent by the client. This is often called the "create" method, and it is the most common method for HTML forms to use in order to send data back to the server.

- PUT—Updates the specified record with the data contained in the request. This is known as the "update" method.

- DELETE—Deletes the record specified by the client on the server. Most people don't feel the need to rename the "delete" method.

In working with any data content, we often use the CRUD acronym to describe basic functions of handling data: Create, Read, Update, Delete. The basic methods of HTTP mirror this concept very well, making them efficient at handling our data management needs.

Headers

In any request, the headers are of importance. Headers contain all sorts of data used by the server to determine the proper response. Each header has a meaning and an impact on the request, but for the most part we never pay much attention to the headers being sent each time we access a website. Here is a snippet of the headers sent when requesting google.com:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: google.com

Connection: keep-alive

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_4) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/43.0.2357.134 Safari/537.36

X-Chrome-UMA-Enabled: 1

X-Client-Data: CIm2yQEIgfjbJAQiptskBCMG2yQEI7YjKAQifl8oB

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8

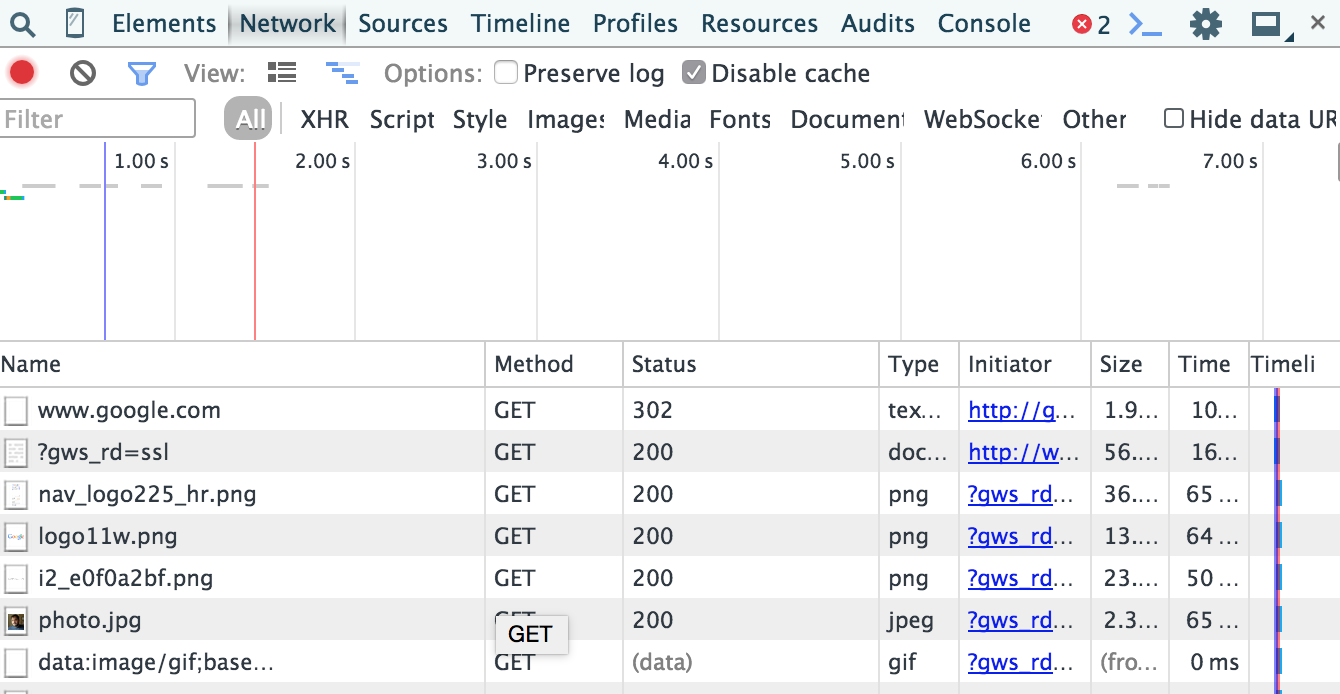

You can easily see the request is using the GET method, and you can probably figure out quite a few more details about the request (language, browser, etc.). You can view the headers used in any request made by your web browser by looking at the Network tab in the Chrome developer tools:

Click any of those requests and you'll see a summary of the request and response including all headers and data. (Please note: Being able to look at what your browser is doing like this can be very helpful when trying to figure out why your API-dependent app is not working properly.)

Sometimes when working with data APIs you will need to set a header. For example, authorization to use an API may involve you sending your API token as an HTTP header. This header is sometimes specified like so:

Authorization: Token 9944b09199c62bcf9418ad846dd0e4bbdfc6ee4b

Most libraries you use to consume data APIs will provide a convenient way to set a header to a specified value. Many frameworks are specifically designed to minimize how much manual management of headers you must perform. When you set configuration options and other setup details you may actually be specifying that the framework or library will include or exclude specific headers. It's worthwhile to be cognizant of what headers are being used in your API requests.

Message Body

The request contains a message body, which contains any data the client is sending to the server. In the case of POST and PUT methods, data is sent to the server for interpretation and then handling (usually it is being saved into the database).

When HTML forms are sent using the GET method, the data from the form fields is serialized into "query string parameters". These are attached with a question mark (?), like so:

http://domain.com/catalog/search?q=slippers&brand=fuzzybunny&gender=male&size=14

In the example above you can see several query string parameters have been defined: q, brand, gender, and size. It is very common to use query string parameters to represent things like search filters. On many ecommerce websites you will notice that the filters you choose in the catalog are easily identifiable in the query string parameters for the catalog page you are viewing.

The URL above could have come from an HTML form with fields called q, brand, gender, and size that was sent using the GET method. This is handy in cases where we want to be able to copy/paste a URL and have our friend see the same results (in this case, a selection of very large fuzzy bunny slippers).

In other situations, it would not be proper to send the data contained in an HTML form as part of the URL. The URL of a request can never be encrypted, since it must be used to route all of the pieces of the request from client to server. Therefore, any data sent using the GET method is going to be visible to all the network nodes those bits pass through. In the case of sensitive information (such as passwords or credit card numbers), it's much better to use POST and PUT so that the message body content can be properly encrypted via HTTPS and much less visible to any nefarious agents.

State(less)

REST is "stateless". (So is the web.) This means that each request to a web server (or a REST API service) must define all of the parameters to receive the desired response. In RESTful services, all of these parameters are packed into the URL and form data. Imagine the number of times you've seen a URL that looks like this:

http://domain.com/profile/username/edit/

Presumably, if domain.com follows best practices, that URL would allow us to edit the profile for the user with the specified username. The server responding to this request would be able to fetch the data for the specified username and serve us back a web page designed to allow us to edit that information. No extra information is required to receive our desired response, and no information from this request will be used in any other response the server sends.

When we edit the information on the page and click submit, we are making a brand new request to the web server. This request defines all of the information the server requires in order to respond to our request. This time, when we send data to the server we include "form data", which is the data collected using HTML form elements (input, select, etc.). This form data provides the information we want the server to put into the database for us.

Data

REST APIs respond with data that can be contained in an HTTP response. This generally means text. The text can return a URL reference to a media file, of course, but then you must actually use that URL properly in your HTML to allow the user to see that media. You might insert an image tag, or a video tag, or whatever other HTML structure is needed to display the media.

The text responses returned by REST APIs tend to either be formatted as JSON (Javascript Object Notation) responses or XML (eXtensible Markup Language) responses. The trend today is toward JSON since it is more easily consumed by Javascript applications, and for our purposes we will expect JSON responses.

Here is a sample API response from OpenWeatherMaps.org for the query api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=seattle,wa,us&units=imperial&id=4717560d:

{

...

"weather": [

{

"id": 701,

"main": "Mist",

"description": "mist",

"icon": "50d"

}

],

...

"main": {

"temp": 61.05,

"pressure": 1018,

"humidity": 63,

"temp_min": 57.2,

"temp_max": 64.99

},

"wind": {

"speed": 4.54,

"deg": 220

},

"clouds": {

"all": 90

},

...

"id": 5809844,

"name": "Seattle",

}

In this example, I have removed a few pieces of the response to make it a little easier to read. (The missing pieces are indicated by the ... lines.)

As you read through this example response, it's pretty easy to see some interesting data fields. We can see that this data object contains several "root level" or "base" attributes: weather, main, wind, clouds, id, name. This is the "current weather" data for Seattle. We are given the ID, which is a more reliable way of not getting confused with the other cities called "Seattle". We also have a weather summary (at the moment "Mist"), current temperature (61.05F), cloud coverage (90%), and more. With this information, we can build a solid weather report.

When this data object is received by our webapp, we will parse the information into a JavaScript object. We can call that object whatever we want (perhaps weatherReport?) and we can pipe that into our view templates like this:

<h1>Weather report for {{weatherReport.name}}</h1>

<p>Current conditions: {{weatherReport.weather.main}}, {{weatherReport.main.temp}}F</p>

And then our users would see this rendered in our webapp:

Weather report for Seattle

Current conditions: Mist, 61.05F

This is just a quick preview of how handy it is to use a JavaScript toolkit to interact with data APIs that deliver JSON responses. We will explore much more about how to make this all work in our webapp over the next few pages of this chapter.